A Rare Medical Emergency: Lessons from a Young Patient’s Mercury Exposure

Mercury, the shimmering silver liquid once widely used in thermometers and barometers, has long captivated human curiosity. Its fluid metallic appearance makes it look harmless, almost playful, as it glides and separates into beads when spilled. Yet, beneath that fascinating exterior lies one of the world’s most toxic substances. Over the years, researchers and doctors have documented its devastating effects on the human body, particularly when exposure occurs in unsafe ways.

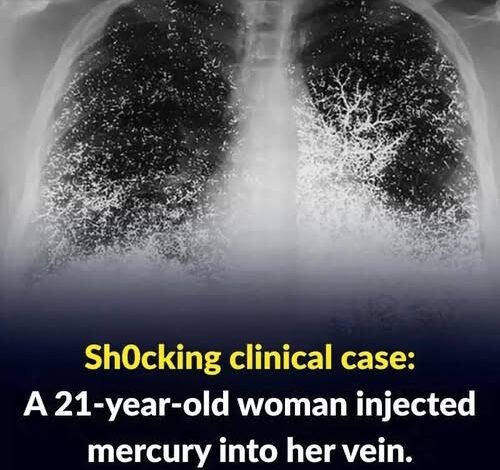

A remarkable and concerning medical case recently underscored this reality. A 21-year-old woman was hospitalized after deliberately injecting liquid mercury into her bloodstream. This rare and alarming event placed her in critical condition and required an intensive response from emergency physicians, toxicologists, and mental health specialists. While cases like this are exceptionally uncommon, the incident serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers associated with mercury exposure, the importance of mental health awareness, and the role of public education in preventing such events.

Mercury: From Fascination to Hazard

For centuries, mercury was valued for its unique properties. Its ability to expand and contract predictably with temperature made it indispensable in scientific instruments. It was also used in early medicine, mining, and even cosmetics. However, modern science has revealed the hidden dangers behind this liquid metal.

Mercury is now recognized as a potent neurotoxin, capable of harming the brain, kidneys, lungs, and immune system. The World Health Organization (WHO) lists it among the top 10 chemicals of major public health concern. As knowledge of its risks grew, mercury was gradually phased out of household products like thermometers and replaced with safer alternatives. Nevertheless, it is still present in industrial processes, some scientific research, and the environment.

A Medical Crisis Unfolds

In the case of the young woman, doctors faced an immediate and complex emergency. According to hospital accounts, she arrived in critical condition after injecting herself with elemental mercury. Unlike accidental exposure from broken devices or contaminated food, which primarily affects the digestive or respiratory system, direct injection sends mercury straight into the circulatory system.

Once in the bloodstream, mercury does not dissolve like medicine or nutrients. Instead, it forms tiny globules that travel through veins and arteries, becoming lodged in the lungs, kidneys, brain, and other organs. This leads to rapid and unpredictable damage. Physicians described the case as exceptionally difficult: such exposures are so rare that medical literature contains only a handful of documented examples, most of them with tragic outcomes.

What Happens When Mercury Enters the Bloodstream?

Mercury’s effects vary depending on the form and route of exposure. In this case, injection represented the most direct and dangerous path. Once circulating through the body, the consequences can be severe:

Respiratory System: Mercury particles can reach the lungs, causing inflammation, chest pain, and reduced oxygen exchange. Inhalation of mercury vapor is already dangerous, but direct circulation through blood vessels amplifies the risk.

Kidneys: These organs, responsible for filtering toxins, bear the brunt of mercury’s load. Prolonged exposure often results in renal failure.

Brain and Nervous System: Mercury has a strong affinity for fatty tissue, including the brain. Neurological symptoms may include tremors, memory loss, confusion, and in severe cases, seizures.

Liver: As the body’s detoxifying organ, the liver struggles to process mercury. This can cause jaundice and impaired metabolic functions.

Doctors emphasize that even small amounts of injected mercury can cause systemic poisoning. Without immediate intervention, such cases are frequently fatal.

The Medical Response

Upon arrival, the woman was treated with chelation therapy, the standard intervention for heavy metal poisoning. Chelating agents such as dimercaprol or EDTA bind to mercury molecules, allowing the body to expel them through urine. While effective to some degree, this treatment has limitations: by the time therapy begins, mercury often has already embedded itself in tissues, making complete removal impossible.

In some severe situations, surgical procedures are attempted to extract visible mercury deposits from tissues. However, such interventions carry high risks and rarely eliminate all contamination. Physicians explained to her family that, even if stabilized, she might face lifelong health consequences, including chronic kidney disease, scarring of the lungs, or neurological impairment.

The Psychological Context

Equally important in this case was the mental health dimension. Injecting mercury is not an act of casual curiosity. Medical professionals stressed that such behavior is a serious indication of psychological distress, possibly linked to self-harm or suicidal ideation.

As part of her care, the patient was evaluated by psychiatrists who highlighted the need for long-term mental health support. Toxic emergencies like this are not solely medical crises—they are also psychiatric alarms. Without appropriate intervention, individuals who attempt such acts may remain at risk of repeating dangerous behaviors.

Public Health Lessons

The incident triggered concern among public health experts. Although mercury is no longer widely available in consumer products, it still exists in laboratories, older households, and certain industries. Lack of awareness or improper handling can lead to accidents, while in rare cases, intentional misuse poses additional challenges.

Public health authorities advocate for stronger education campaigns about mercury’s dangers. Communities must understand that while mercury’s silvery appearance may look intriguing, it is far from safe. Its misuse can lead to lifelong consequences, not only for the person exposed but also for those around them, as improper disposal can contaminate homes and the environment.

Mercury’s Toxic Forms Explained

To fully appreciate the risks, it is useful to distinguish between the three primary forms of mercury:

Elemental Mercury (Liquid Metal): The shiny liquid seen in old thermometers. Dangerous when inhaled as vapor or directly introduced into the body, as in this case.

Inorganic Mercury Compounds: These salts and oxides are used in some industrial chemicals and, historically, in skin-lightening creams or antiseptics. They are harmful if ingested or absorbed.

Organic Mercury Compounds (e.g., Methylmercury): Formed when mercury enters the food chain, especially in fish. Chronic exposure causes neurological harm and developmental issues in children.

All forms are toxic, but the route of entry determines the scale of damage. Injection of elemental mercury bypasses natural barriers, making it uniquely catastrophic.

Historical Cases of Mercury Poisoning

This case is not the first to draw attention to mercury’s dangers. Several historical events demonstrate the element’s deadly potential:

The Mad Hatter Syndrome: In the 18th and 19th centuries, hat makers who used mercury nitrate to treat felt developed neurological symptoms such as tremors and mood swings, giving rise to the phrase “mad as a hatter.”

Minamata Disease (Japan, 1950s): Industrial mercury waste contaminated local seafood, causing thousands of cases of neurological disease in coastal communities.

Karen Wetterhahn (1997): A chemistry professor at Dartmouth College accidentally spilled a few drops of dimethylmercury on her glove. Despite immediate decontamination, she died less than a year later, showing how potent mercury compounds can be.

These events illustrate that mercury poisoning, whether accidental or intentional, has profound and often irreversible outcomes.

Mental Health and Toxicology: A Dual Challenge

This case also shines light on the intersection of mental health and toxicology. When patients expose themselves to dangerous substances, healthcare providers must treat both the physical damage and the underlying psychological drivers.

Experts advocate for integrated care: toxicologists to manage poisoning, psychiatrists to address mental health needs, and social workers to provide long-term support. Communities also play a role by reducing stigma around mental health and encouraging people to seek help before crises occur.